Nobel Prize in Chemistry 2014 for Max Planck researcher Stefan Hell

When Stefan Hell got the call on 8 October from Stockholm informing him that he would be receiving this year's Noble Prize in Chemistry, he was sitting at his desk concentrating on a publication. "The first thought is of course this is a hoax," recalls Stefan Hell of the first moment. But the fright soon gave way to tremendous happiness. The physicist says "I am very delighted that the work from me and my coworkers receives the highest award that one can achieve as a scientist." Max Planck President Martin Stratmann emphasizes: "This is a wonderful recognition of the pioneering achievements of Stefan Hell. A researcher is recognized who had the courage to surmount many obstacles, paving new paths, and challenge established dogma". Hell is the 18th Nobel Prize winner of the Max Planck Society. The Chemistry Noble Prize is endowed with eight million Sweden Crowns (about 880,000 Euros).

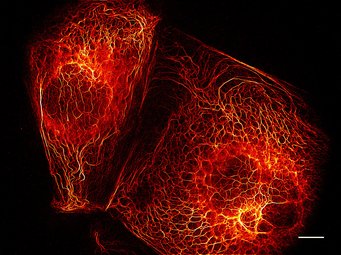

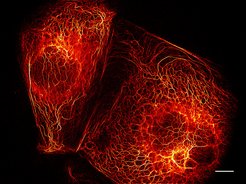

With the invention of the STED (Stimulated Emission Depletion) microscopy experimentally realized by Hell in 1999, he has revolutionized light microscopy. Conventional light microscopes reach their resolution limit when two similar objects are closer than 200 nanometers (millionth of a millimeter ) to each other because the diffraction of light blurs them to a single image feature. This limit discovered about 130 years ago by Ernst Abbe – and chiseled in stone in a memorial in Jena (Germany) – had been considered an insurmountable hurdle. The same limit by diffraction also applies to fluorescence microscopy which is frequently used in biology and medicine. For biologists and physicians, this meant a massive restriction – because for them the observation of much smaller structures in living cells is decisive.

The 51-year-old physicist Stefan Hell was the first to radically overcome the resolution limit of light microscopes – with an entirely new concept. STED microscopy, invented and developed by him to application readiness, is the first focused light-microscopy method which is no longer fundamentally limited by diffraction. It allows an up to ten times greater detailed observation in living cells and makes structures visible that are much smaller than 200 nanometers. "Back then I intuitively felt that something has not been thought through thoroughly," Hell recalls.

In order to overcome the phenomenon of light diffraction, he and his team apply a trick. The focal spot of the fluorescence excitation beam is accompanied by a doughnut-shaped „STED beam“ that switches off fluorophores at the spot periphery, by effectively confining them to the ground state. In contrast, molecules at the doughnut center can dwell in the fluorescence „on“ state and fluoresce freely. The resolution is typically improved by up to ten times compared with conventional microscopes, meaning that labelled protein complexes with separation of only 20-50 nanometers can be discerned. As the brightness of the STED beam is increased, the spot in which molecules can fluoresce is further reduced in size. As a consequence, the resolution of the system can be increased, in principle, to molecular dimensions.

By developing special fast recording techniques for the STED microscopy, Hell’s team further succeeded in recording fast movements within living cells. They reduced the exposure time for single images in such a dramatic way that they could film in real-time the movements within living nerve cells with a resolution of 65 to 70 nanometers – a 3 to 4 times better resolution compared to conventional light microscopes.

With his outstanding work Stefan Hell has pushed open a door towards new insights into what happens on the molecular scale of life – a door which was believed for a long time to be non-existent. STED microscopy offers plenty of potential for research on disease or the development of drugs, Hell explains. "If one can directly observe how a drug affects the cell, the development time of new therapeutic agents could be reduced enormously." (cr)

About the awardee

Stefan W. Hell (born in 1962) received his doctorate in physics from the University of Heidelberg in 1990, followed by a research stay at the European Molecular Biology Laboratory in Heidelberg. From 1993 to 1996, he worked as a senior researcher at the University of Turku, Finland, where he developed the principle of STED microscopy. In 1997, he moved to the Max Planck Institute for Biophysical Chemistry in Göttingen (Germany), where he set up his current research group dedicated to sub-diffraction-resolution microscopy. He was appointed a Max Planck Director in 2002 and currently leads the Department of NanoBiophotonics at the Max Planck Institute for Biophysical Chemistry and the Department of Optical Nanoscopy at the German Cancer Research Center in Heidelberg (Germany). He is an honorary professor of experimental physics at the University of Göttingen and adjunct professor of physics at the University of Heidelberg.

Stefan Hell has received numerous national and international awards, including the Prize of the International Commission for Optics (2000), the Carl Zeiss Research Award (2002), the Innovation Award of the German Federal President (2006), the Julius Springer Award for Applied Physics (2007), the Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz Prize (2008), the Lower Saxony State Award (2008), the Otto Hahn Prize for Physics (2009), the Ernst Hellmut Vits Prize (2010), the Familie-Hansen-Prize (2011), the Körber European European Science Prize (2011), the Gothenburg Lise Meitner Prize (2010/11), the Science Prize of the Fritz Behrens Foundation (2012), the Paul Karrer Medal (2013), the Carus Medal of the German National Academy of Sciences Leopoldina (2013) and the Kavli Prize in Nanoscience (2014). He was elected into the Hall of Fame der deutschen Forschung in 2014. Stefan Hell has honorary doctorates from the Universities of Turku (Finland) and Vasile Goldis (Romania) as well as the from University Polytehnica of Bucharest (Romania).